COVID-19 is a Category 5 hurricane. We wear masks to shield against the virus much like protecting windows with plywood. Masks might protect our health but don’t do much for our fragile psyches. We strive to feel physically safe in our shelters, but we know there is mayhem out there. Millions and millions of jobs are lost, and no one knows how long it will take to recover. And while uncertain futures are pondered behind precariously protective masks, videos of threatening and deadly acts go viral. COVID’s seething undercurrents take a different shape. . . . a human torrent fills the streets, saying enough is enough. . .

There are and will be countless narratives about the recent happenings in America’s cities. But I am not one to add to the collection. Instead I’m moved to write about resiliency, about perseverance, about strength, indeed, about the gift of beauty in the midst of mayhem.

I’m moved to write about Jock Soto, world-renowned dancer, born in Gallup, New Mexico to Navajo mother Josephine Towne and Puerto Rican father Jose Soto.

Jock Soto is now 55, retired from the stage but in demand as a teacher of aspiring and professional dancers in New York and around the world. Now, during COVID, he teaches via Zoom from his and his husband Luis Fuentes’s New Mexico sanctuary in Eagle’s Nest, not far from Taos.

I first saw Jock Soto dance in the late 1980s at the former New York State Theater (now the David H Koch Theater) at Lincoln Center. I saw him not long after he was appointed the youngest principal dancer of the New York City Ballet at the time (and the last male dancer to have been handpicked by the late George Balanchine, the company’s founder and its spiritual leader in perpetuity).

I had been invited to the performance of Balanchine’s Symphony in C featuring Soto by a dear friend visiting from out of town. My friend knew that I loved ballet, and that I had yearned to see Soto. All three of us (Soto, my friend and I) had Southwest legacies, and Soto, so early in his career, was already legendary. The performance showed us why.

During a crisis, our minds tend to journey back to earlier fears and earlier joys. I have been thinking of that gorgeous 1980s performance because New York at that time was experiencing another hurricane . . . AIDS, displacement, a struggle to recover after headwinds of mismanagement and neglect brought the city to its knees.

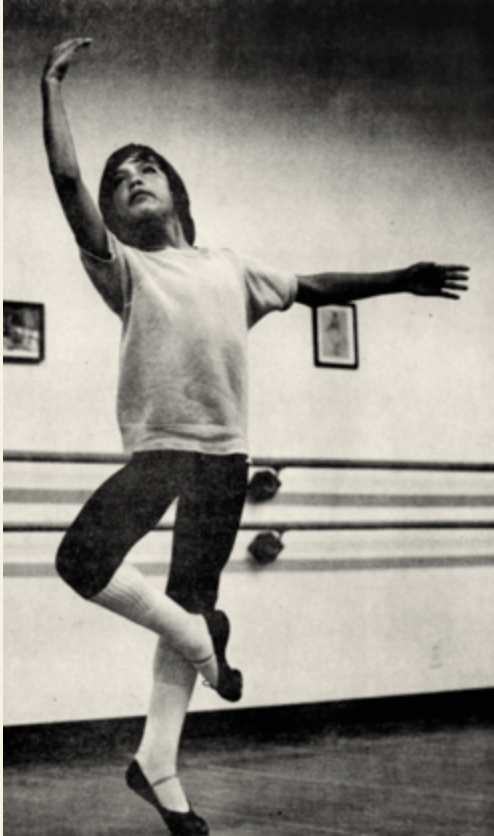

Jock Soto had arrived in New York in the late seventies, when the city was probably at its most down and out (until now). He was 13 years old. He’d been scouted by the School of American Ballet after being spotted in a class in Phoenix. His family had moved there specifically to give him a chance to fulfill his dream of becoming a ballet dancer, a dream he developed at the age of 5 after seeing the great Edward Villella on television.

His family’s journeys were centered on artistic dreams . . . Jock’s as a dancer, his brother’s as an actor. His parents’ self-appointed role was to keep the doors to dream fulfillment open. Jock tells his story eloquently in his memoir Every Step You Take (told with Leslie Marshall, Harper Collins, 2011).

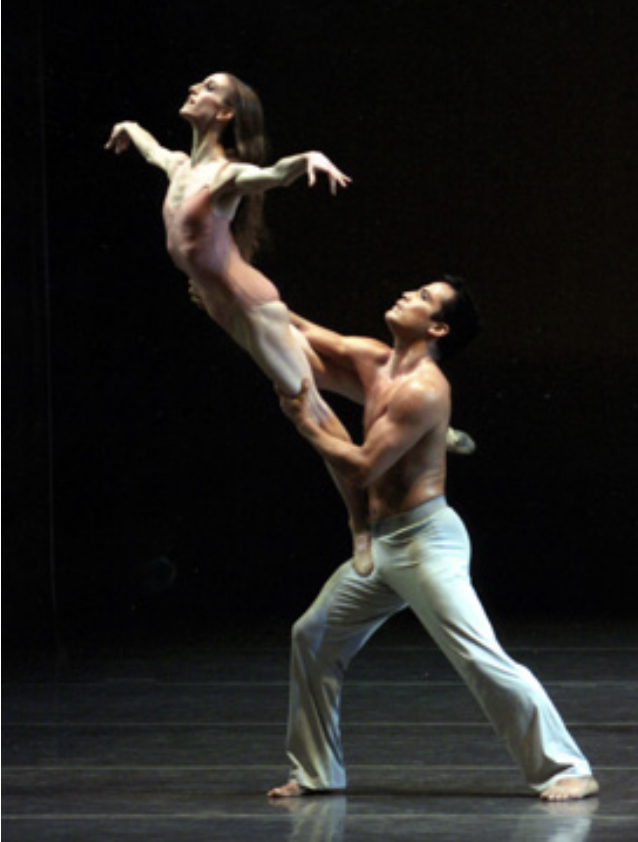

Though he started out in New York with his family in 1978, life in New York became too much for them, and he was left there at 14 to manage on his own. He became a principal dancer of the company six years later, which tells you how he managed. Many, many ballets were choreographed based on his capacity to do just about anything that a choreographer could conceive of. And unlike some of the other superstars of his era, such as Baryshnikov, Jock had the reputation as one of the best ballet partners in the world. The greatest of ballerinas relied on him to catch them, support them, make possible the otherwise impossible, to let them shine. As a dancer, Jock is a rare combination of greatness without ego. What came through in his performances was not only his unparalleled skill, but generosity beyond measure.

Jock’s Navajo clan is To’aheedliinii, which means Water Flowing Together (there’s a documentary about Jock with this title. It’s nearly impossible to obtain, but a clip is available on YouTube).

The photo to the right (from danceviewtimes.com) shows Soto and ballerina Wendy Whelan flowing together in choreographer Christopher Wheeldon’s “After the Rain.” The year was 2005, Jock’s last year on the New York City Ballet stage.

I read somewhere that members of the Water Flowing Together clan are joyous, sexy, outgoing and dominant . . . all things that Jock conveyed when I saw him dance all those years ago.

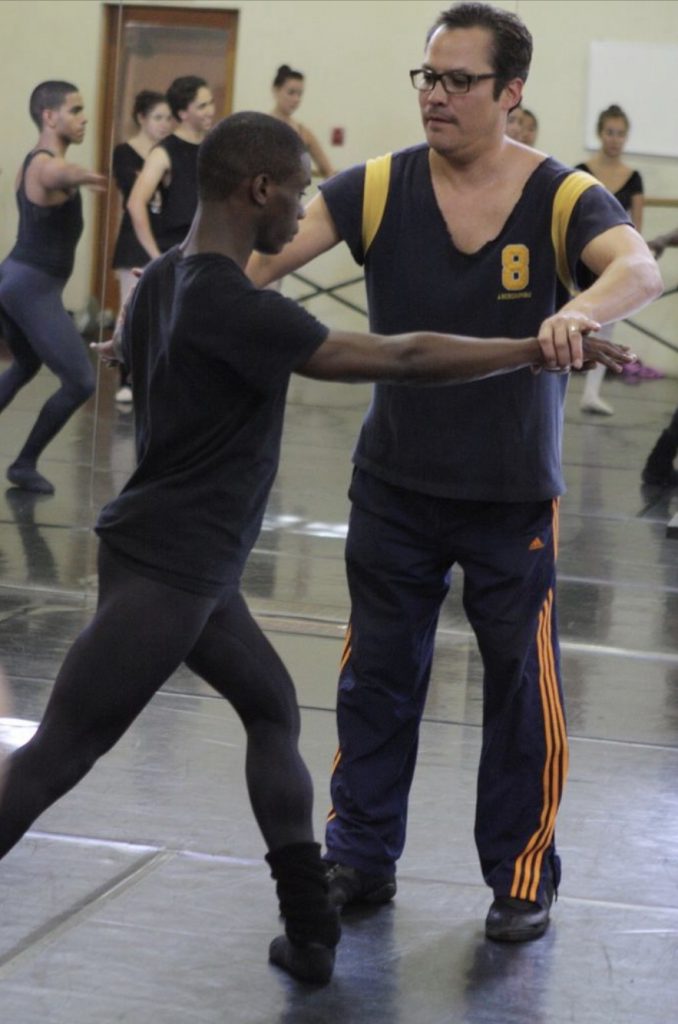

Now Jock teaches dancers at all levels. Perhaps most notably, he teaches master classes in partnering . . . a skill that demands perfection lest everything fall apart, a skill that demands that ego be tucked away to showcase another’s ability to spin and fly.

For ten years, Jock taught a 4-week course in ballet to indigenous students in Banff and Toronto, students who never knew a ballet position before his class and at the end knew enough to perform admirably for an audience. Jock told me that it was his mother’s dream that he teach ballet to indigenous peoples. Who better than Jock, who started dancing the hoop dance at the age of 3 and became a principal dancer of NYCB at age 20, to point the way to the beauty and empowerment of movement?

Jock Soto has much to teach.

Last year, the LGBT group Dine Pride gave Jock Soto their Dine Pride Champion Award, and he had a message for the audience in Window Rock, the Navajo capital: “What my mother always said was, ‘Pursue your dreams and walk in beauty’.”

I envision a poster with his picture and his words, with the added directive “Move!”, displayed in every chapter house on the Navajo Nation, where diabetes and heart disease are rampant.

As the streets of American cities are filled with citizens pleading for change, as the Navajo Nation copes with the worst COVID statistics in the United States, messages like Jock Soto’s can become drowned out by cries of despair and anger. But his are words that all of us need to remember. And Jock can teach all of us something else: flowing together, partnering, is a skill that we all will we need if, at the end of COVID, we are going to fight our way back from disaster and do our damnedest to walk in beauty out of the storm.