When you have an interest that you pursue on Google, the Google gods remember, and sometimes they surprise you with related news items that pop up on your Google home page.

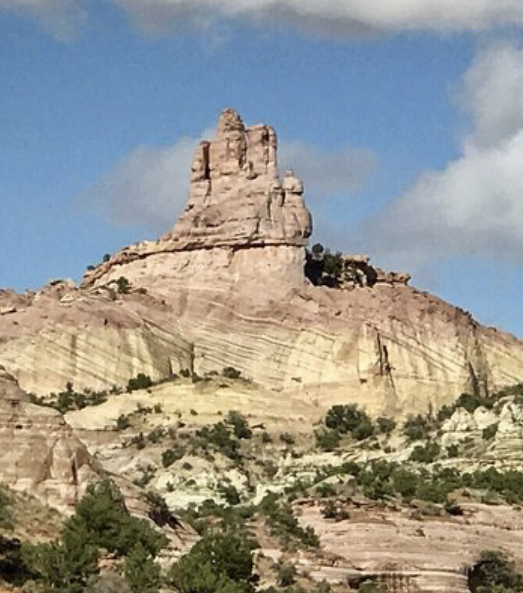

The Google gods know that I have an interest in a small town named Church Rock (population per 2010 census: 1,128). Church Rock lies in Navajo territory on the outskirts of Gallup, New Mexico.

Google probably doesn’t know (but maybe does) that my interest in Church Rock stems from my having taught in the town my first year out of college, but no matter. Google knew I would be intrigued by an article that came out in the Navajo Times this week. The article’s subject is a nitrile glove factory in Church Rock that is now manufacturing medical gloves and shipping them to health care facilities in the Navajo Nation and other US locales struggling to cope with COVID-19. The locales include my home state of New York. (See Navajo Times article on Navajo glove facility.)

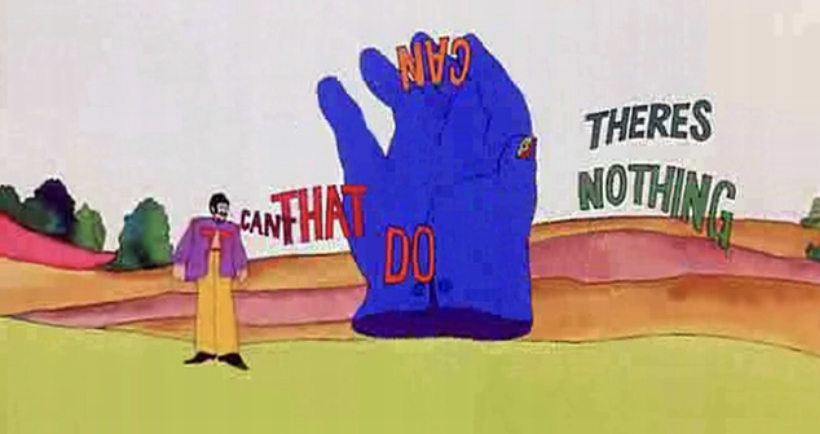

Phase One of a joint venture between the Navajo Nation and a company called Rhino Health, LLC, is primed to make 60 million pairs of blue nitrile gloves a year. Per the Navajo Times piece by reporter Donovan Quintero, the Church Rock factory is now churning out 8,000 pairs of gloves an hour and running around the clock. They are striving to keep up with demand while dealing with a shortage of raw material. (Materials have to be shipped from South Korea, home of Rhino Health’s parent company.)

When Phase Two is completed, adding significantly more manufacturing space, Church Rock will be generating 1.3 billion pairs of blue sterile gloves a year for medical use.

Because of the Navajo Times article, I Googled keywords “nitrile” and “Church Rock” and found that in 2018, about two years before anyone had ever heard of COVID-19, the Navajo Nation invested $19 million for Rhino Health LLC to build its Church Rock facility that will eventually employ 350 Navajo workers (the state of New Mexico kicked in another $3 million).

News about the Navajo-Rhino Health joint venture was reported in the Albuquerque Journal, and later in the Navajo-Hopi Observer, but never leaked beyond regional boundaries. In the event other media don’t report how Navajo workers in Church Rock are helping first responders face the battle against the virus by providing protective gloves, I feel compelled to leak it here.

You may not know this about the Navajo town of Church Rock, but in July 1979, a few months after the famous Three Mile Island nuclear incident, Church Rock suffered a devastating radioactive contamination event courtesy of the United Nuclear Mine Corporation.

In 1979, the dam holding back tailings at United Nuclear’s Church Rock mine ruptured, sending 1100 tons of solid radioactive waste and 94 million gallons of radioactive solution into the local water sources and beyond (as far away as 50 miles downstream).

The spill resulted in the largest release of radioactive material in US history (see US government reports, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_Rock_uranium_mill_spill).

In the world at large, the Church Rock United Nuclear incident is second only to Chernobyl in terms of long-lasting devastation.

Today, if you ask the Google gods “What’s the worst nuclear disaster?” your search result will likely bring up a Business Insider article that describes the incidents in Chernobyl and Fukushima, the latter caused by the 2011 Tohuku earthquake and tsunami. The article says that Three Mile Island was not nearly as devastating as those two calamities (see: https://www.businessinsider.com/chernobyl-fukushima-three-mile-island-nuclear-disasters-2019-6).

The Business Insider article doesn’t once mention what happened in Church Rock, New Mexico forty years ago. In Church Rock, the effects of the accident (effects that include kidney disease, cancer, fear of having children . . . ) are being felt to this day (see August 2019 VICE article on lasting impact of Church Rock mine disaster).

A central tenet of Navajo belief is the uniting principle of K’e, or kinship. It begins with caring for the immediate family, extends to the clan, and from there extends to the community as a whole. K’e, in essence, is the concept of how we are all related and thus responsible for each other.

In 1979, when it came to nuclear disasters creating a sense of community, a sense of K’e, the whole country fretted about the dangers facing Americans who lived near Three Mile Island. But what happened in Church Rock four months later didn’t penetrate the country’s consciousness at all. The national media barely mentioned the accident back in the day. It seemed that the people of Church Rock, who faced overwhelming devastation–dead livestock, contaminated water, early mortality–were outside the realm of Americans’ concern. Today, forty years later, the media is paying more attention. But while HBO’s Chernobyl won a slew of Emmy Awards, I haven’t read that there’s any series planned on what happened at Church Rock within our own nation’s borders.

In 2020, we are united in our knowledge that COVID-19 is affecting all of us, that the virus is shaping our immediate if not distant future. New York State may be the US epicenter of the virus, but we know that no region of the country is immune, especially not the Navajo Nation.

On the Navajo reservation, a territory of 27,425 square miles where about 40% of the population have to drive a great distance to get a supply of water, COVID-19 cases are spiking (see LA Times on Navajo COVID-19 crisis and NPR article on COVID-19 and Navajo Nation). Nonetheless, the people of Church Rock are working hard to ensure that the folks on the front lines as far away as New York State are safe.

I just thought you should know.