In 1975, when I taught on the Navajo rez outside of Gallup, the state of New Mexico didn’t fund kindergarten, let alone art education. If I wanted my kids to paint, weave, sculpt, then it was up to me to add art to the list of subjects I was hired to teach in my classroom. It is worth noting without too much emphasis that I landed my teaching job on the rez after graduating from Vassar, where I never took a fine art class and would have been an idiot to think I belonged in the college’s creative arts talent pool.

Though I wasn’t an anthropology major (and Native Studies didn’t exist back then) I knew that art and craft loomed large in Navajo culture. So not wanting to be a total fraud, I signed up for a night class called “Indian Painting” at the University of New Mexico Gallup Branch.

It turned out I was one of the few female students in the class as well as one of the youngest. I was not the only white person, however. There was one other, that being our instructor, whose name I remember to this day. I will refer to him by his initials, LS, so as not to disturb his ghost.

LS was a New Mexico state trooper. He looked like he could be an extra in a Hollywood film about Texas Rangers. But LS was an ARTIST. You could tell because he dressed all in black—black jeans, black shirt, black cowboy boots. And he had a shiny Navajo silver buckle on his black belt, which I guess advertised his cred for teaching art to a class of mostly Navajos and Zunis. His stride and swagger, though, spoke of his true profession.

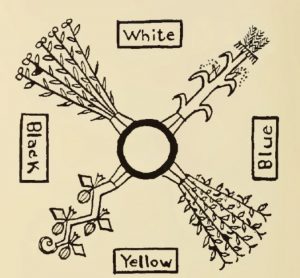

LS had a formula he wanted all of his students to copy. His formula was simple: Paint four images of Pueblo pots, one in each corner of your canvas. And in the middle of the space, paint an “Indian” sun symbol (e.g., the emblem of the State of New Mexico). Toss in some corn and lightning symbols in the rest of the space, and voila: surefire Indian painting success! LS showed us his many Indian paintings and boasted that he made up to $75 a piece. If he could do it, we could too!!

I was seated at a worktable (no easels needed apply) with three males, one of whom was my age. The other two seemed to be in their late thirties or early forties.

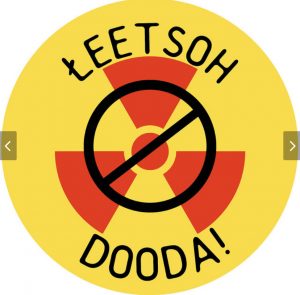

As I said, I was a young graduate of Vassar College, and though I was the lone female and lone white at the table, I said to my tablemates: “Are you going to put up with this??” Everyone laughed, and we made a communal decision: No, we weren’t. We decided to start a new art movement, a Navajo take on Dada (my age mate at the table, who would eventually become a renowned non-traditional silversmith, knew all about Dada). We called it DOODA (pronounced doh’dah’), which is Navajo for NO. An older tablemate had a buddy at the table in front of us and roped him into our DOODA movement.

We churned out paintings that made LS speechless, shaking his head in disappointment. When he strutted around giving tours of the assembly line he called “Indian painting,” LS brusquely guided his guests past our tables without a pause.

My tablemates and I painted masterpieces of anything we wanted. Images of Navajo Yei figures as electrical towers, of horses that flew into the heavens, of sheep lying shot and dead in the desert said DOODA to our State Trooper art instructor. While we painted, we discussed topics of the day, circa 1975: Lynette Squeaky Fromme, Sarah Jane Moore (female would-be assassins of Gerald Ford). We told jokes, named favorite comedians (one tablemate said he prayed that George Burns would live to at least his 100th birthday).

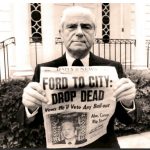

My final art project as a 22 year old Jewish transplant from the East Coast? Well, this was 1975, and New York City was on the brink of default, which is one reason why I came to the rez in the first place. New York City laid off 2000 teachers when I graduated from college, and I had decided that if I couldn’t teach in New York, I didn’t want to teach in any city at all.

So as an adios to LS, I painted “Grandfather Gods Take Manhattan,” a New York cityscape lit by a Navajo moon and shrouded in clouds of doom, with Navajo Grandfather Gods (Yeibicheii) flying overhead with their healing bundles to the rescue (see above). I’d also cut out and attached a photo of New York Mayor Abe Beame, but the mayor somehow disappeared from the work during my many moves years hence.

LS gave my rudimentary work a B+, with no comments.