A while ago I’d learned that one of my former employers, Northland Press in Flagstaff, AZ, closed its doors after shifting focus from books on the art and culture of the American West to children’s books.

I’d worked at Northland in the 1970s, first as assistant editor under Rick Stetter, who went on to a great future in regional publishing. When Rick left, I took his place as editor under the direction of Northland’s founder, Paul Weaver.

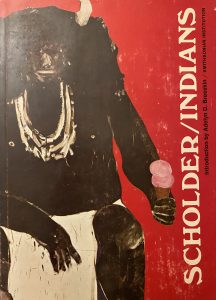

The artists covered in Northland’s books included a long roster of Native American painters, sculptors, potters and jewelry designers: Fritz Scholder, R.C. Gorman, Charles Loloma, Allan Houser, Helen Cordero, Grace Medicine Flower . . . Weaver and company presented the depth and scope of these artists vibrantly, on pages of fine-coated paper stitched together between clothbound, embossed covers.

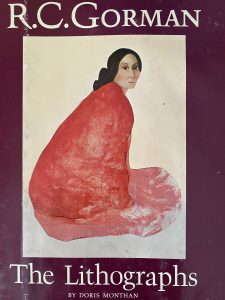

The last book I worked on at Northland before heading out the door was R.C. Gorman: The Lithographs by Doris Monthan, published in 1978.

I have mixed feelings about R.C. Gorman, a prolific Navajo artist who seemed to churn out images of women in his sleep. He died in 2005 at age 74.

When I lived in New Mexico, Gorman ran his art enterprise from his Taos spread and threw lavish parties there. (I’d missed the boat on another Northland-Gorman outing: Nudes and Foods: Gorman Goes Gourmet, published in 1981. ) Gorman’s legacy is tainted by an ultimately dropped FBI investigation into his possible involvement in a pedophile ring, but that’s for someone else to discuss.

My own reservations about Gorman aside, my late mother adored his work, which is why I gave her my copy of the Gorman lithograph book, a parting gift from Northland that’s now back on my shelf.

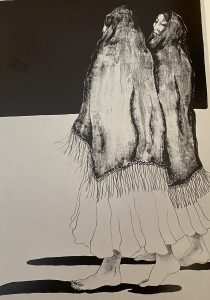

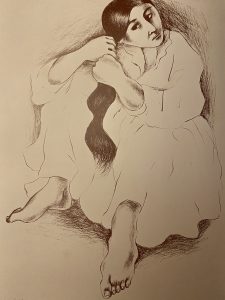

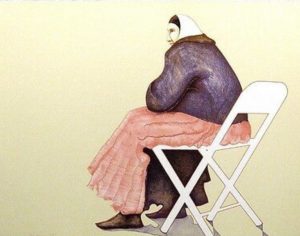

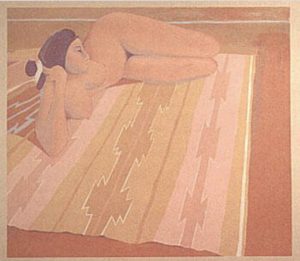

My parents had purchased and framed a poster of one of Gorman’s ubiquitous Navajo women to decorate a wall of their old condo outside of Fort Lauderdale, FL. And when I saw it hanging there so many years ago, I wondered how many other Florida condos featured a blissful Gorman female, soft-hued, serene, drawn in simple lines (but barely any on the face), hands and feet large but neither calloused nor veiny.

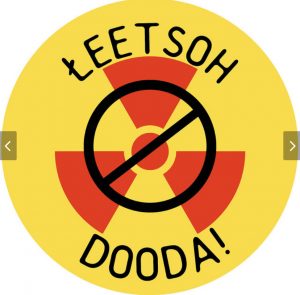

My problem with Gorman’s work is that there’s no grit, no irony, not a lot that’s honest when it comes to his portrayals of Navajo women, of the toughness it takes to run a sheep and horse ranch off the power grid, in a land of harsh sun and wind, with no running water. Like, none of Gorman’s women cover their feet. What’s with bare feet in the desert?

A younger Navajo contemporary of Gorman, artist Ed Singer nails the character of the Navajo matriarch, and Navajo life generally, in many of his works. (You can query about Ed’s work at artjuicestudio@gmail.com. Disclosure: Singer is a friend of mine).

I don’t know if anyone asked Gorman back in his heyday, but after being raised on the rez, did Gorman believe his depictions of Navajo women truly paid them homage or was it that they proved so ideal for his bank account that he couldn’t stop them coming?

Even today, many Florida, Scottsdale, and suburban homes have a poster of the “native woman ideal by Gorman” on the wall, or on coasters under a served round of drinks. I wonder, if he were alive today, would Gorman be like Peter Max, compulsively striving to keep the coffers filled by churning out his pretty women to be auctioned off on cruise ships?

Last week, I pulled R.C. Gorman: The Lithographs off my bookshelf and browsed its pages. I’d forgotten that it included not only the lithographs with women as subject matter, but also a few rug designs, a few male nudes and other assorted “native life” images. But the eyeopener for me was this quote from R.C. Gorman in the biography section:

Said Gorman: “I have been using the design motifs of Indian rugs and pottery for my paintings because one day these things are going to be no more. They are going to be lost, and it is going to happen soon. It’ll be a white America by A.D. 2000. The Indian art that people are enjoying—the rugs and pottery—are no longer going to be there. . . I am amused that I sell my rug paintings for more than the rug sells for; perhaps the paintings are worth more in the long run. Moths hate polymers.”

Hubris R.C. Gorman had aplenty, prescience not so much.

The above-mentioned quote prompted me to do a web search. There’s a gorgeous 36” by 23” rug by contemporary Navajo weaver Ruby Watchman for sale on navajorug.com for $3765.

There’s a 27.5” x 30.25” Gorman lithograph of naked woman sprawled out on a Navajo rug for $1200 on herndonfineart.com.

A.D. 2000: a “white America “. . . “Indian art that people are enjoying . . . no longer going to be there. ” . . . Well, R.C., too bad you weren’t able to stick around for Ruby Watchman, Cleo Johnson, Donald Yazzie, Sadie Charlie . . . and so many more contemporary Navajo weavers in full and glorious view on Pinterest.

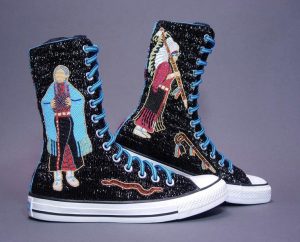

And too bad you didn’t live to see the heights where native women like Wendy Red Star (see wendyredstar.com) and Teri Greeves (see terigreevesbeadwork.com) are taking things in terms of craft and native female presence.

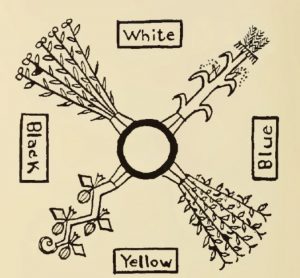

It’s 2020 now. R.C. Gorman, wherever you are, you may want to start covering women’s feet with these: