Before heading out to the Southwest, my sister and I had buttoned up our itinerary and had marked it with highlighter on the AAA Indian Country Guide Map.

Here’s how one segment of our trip was supposed to go:

After exploring Mesa Verde on its opening day of the season, we’d planned to hang out in Cortez for a night and enjoy the company of artists Ed Singer and Sonja Horoshko. The next morning we were to head down to Shiprock for a visit with artist and poet Gloria Emerson. From there, we were to head south to Gallup, New Mexico on the old Route 66.

I had lived just outside of Gallup in the 1970s, and I had wanted to see how it had changed.

For one thing, I knew that since the long ago days when I taught at an Gallup/McKinley County elementary school, an Arab community had grown in Gallup to the point of building a mosque. Arab trading in Gallup and nearby Zuni had been in its infancy back in the 1970s. It seemed worth it to drive down to Gallup just to see a mosque in a town that now wore with pride a new moniker of “The Most Patriotic City in America.” This new banner must be an uplift for a town burdened for years by quite another nickname: “Drunk City.”

Gallup, New Mexico has a population of about 20,000. It has almost 40 liquor licenses.

These days, Gallup also has just under 50 payday loan establishments. Back in the day when I lived in Gallup, the traders were the main moneylenders, doling out cash for pawn. Often, the lender and the borrower knew each other by name, and in some cases inquired about each other’s families. Could that be true in an establishment named “Cash Cow” or “Check ‘n Go” or “Fast Bucks”? I had read that some Navajos were paying over 1000% interest to payday lenders in Gallup, borrowing from one to pay another.

Bleak times, but I was nostalgic nonetheless. Despite envisioning how things had deteriorated for so many in Gallup since the 1970s, I had expected that some good memories would be jolted awake by seeing the place again. I am in my sixties, a time of reaching back to the glory days of youth. Besides, I really wanted to see that mosque.

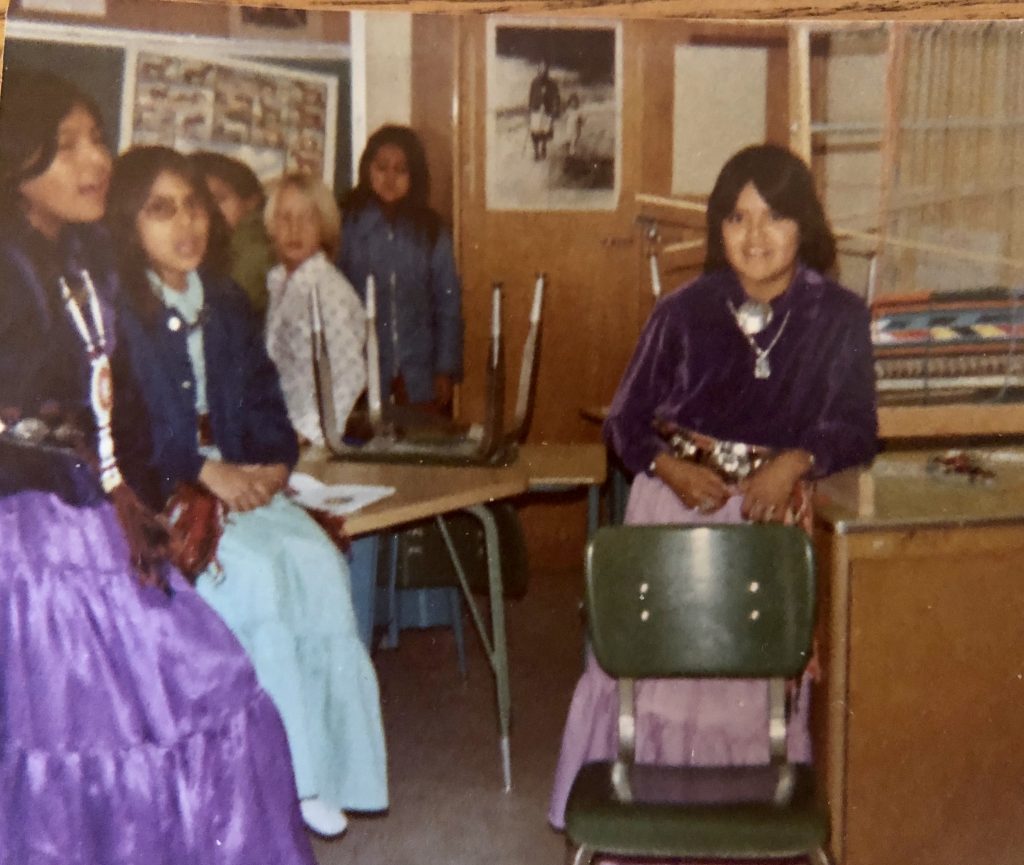

The school where I had taught right out of college in the ’70s served a small Navajo village east of town. The school principal’s principal interest was selling Navajo jewelry out of his briefcase when attending school administrator conferences. He let all of us teachers teach anyway we wanted, as long as his elementary school team won basketball games. My classroom was filled with student art, weaving, and overall happy times.

Soon after I left, the community where I’d lived and taught suffered what remains the worst nuclear disaster on US territory. (See The Church Rock Uranium Mine Disaster of 1979.) The nuclear situation apparently resolved enough for the tribe to open a casino near the disaster site in 2008.

But having done a bit of research before our trip, I felt that I had to see that Gallup actually had a Starbucks these days, and maybe even a decent restaurant. To the strains of a virtuoso female fiddler from Japan, I’d learned to do the two-step at a country western club in Gallup back in the day. Was the club still there under a different name? Was the railroad station, now the cultural center, as attractive as it seemed in the pictures?

Per our trip itinerary, I was going to find all these things out after leaving the town of Shiprock.

But then we actually arrived in Shiprock, where we met up with Gloria Emerson in the parking lot of the medical center. From there we drove around the corner for a bite of lunch before heading out to Gloria’s property east of town. It was time enough to see that the times had not been kind to this grey Navajo town, which looked pummeled by a ruthless fighter, its bones cracked from the impact.

Shiprock ranks third in the United States in the percentage of Native Americans living below the poverty line. The Navajo Housing Authority had built a set of over 90 homes there that had to be torn down due to poor construction, high wind damage, and vandalism. There’s a casino nearby that might be helping the local economy, though it’s hard to tell.

My sister, niece and I were all too anxious to follow Gloria out of town to her desert oasis.

“Why do you want to go to Gallup?” Gloria asked when the topic came up during conversation. “I haven’t been there in a long time.”

I told Gloria about wanting to see the mosque.

“I don’t know about that,” she said. I showed her a picture of it on line. She nodded. “Looks interesting. You know, there’s a community of nuns who are trying to do some good work in the north side of town.” I remembered the north side of Gallup. That’s where the bars were that we teachers were warned about.

We told Gloria that we were heading from Gallup to Chinle, to Canyon de Chelly.

“There’s a beautiful road down through the Red Valley,” Gloria said. “Route 12. You should take it. It’s so, so beautiful.”

Gloria is 80 years old. She knows every corner of Navajoland.

When we were heading away from Gloria’s, my sister asked the question: “How important is it for you to go to Gallup?”

I know what she wanted me to answer, and I looked at my niece who had been much saddened by Shiprock.

I thought a few seconds. What would I actually learn that I didn’t already know? What were the chances that the town would ignite a spark of joy over some memory from days long past? I was with my niece, who is the age I was when I lived in an around Navajoland. I was seeing things through her eyes. And all I could envision her eyes being filled with in Gallup were tears.

“Let’s take Route 12,” I said. “It’s just out of town, on the right.”

The road through the Red Valley was one of the most spectacular any of us had ever seen. Thank you, Gloria. Thank you, wise woman.

I can look at pictures of payday loan storefronts to my heart’s content on Google, should I ever get nostalgic for the place where I began my adult life.